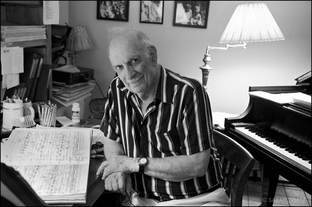

Aaron Copland (1900-1990), the son of Russian-Jewish immigrants, grew up in New York City. In the summer of 1921 he attended a course in Fontainebleau, France, where he met Nadia Boulanger. He moved to Paris for three years in order to study with Boulanger. When he returned to the US, during the Great Depression, he found that the modernist style that he had adopted in Paris was not gaining him the wide audience or financial rewards that he desired, and he soon chose to write in a more accessible style. Works written in this ‘populist’ vein include his ballets Appalachian Spring, Billy the Kid and Rodeo, his Fanfare for the Common Man and Third Symphony

During the late 1940s, Copland became aware that Stravinsky and other fellow composers had begun to study and adopt Arnold Schoenberg's twelve-tone techniques. Copland incorporated these techniques into some of his works in the 1950s and 1960s, but used the tone rows as sources of inspiration for melodies, rather than trying to write strictly serialist music.

Copland’s music often blends classical, folk, Latin American and jazz idioms. Copland was keen to find a way to write scores that epitomized American music. He often achieved this through his slowly-moving, open harmonies that seem to evoke wide American landscapes.

During the late 1940s, Copland became aware that Stravinsky and other fellow composers had begun to study and adopt Arnold Schoenberg's twelve-tone techniques. Copland incorporated these techniques into some of his works in the 1950s and 1960s, but used the tone rows as sources of inspiration for melodies, rather than trying to write strictly serialist music.

Copland’s music often blends classical, folk, Latin American and jazz idioms. Copland was keen to find a way to write scores that epitomized American music. He often achieved this through his slowly-moving, open harmonies that seem to evoke wide American landscapes.

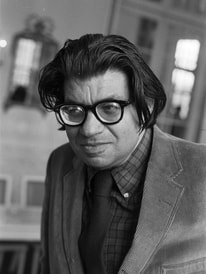

George Crumb (b.1929) is well-known for creating unusual timbres in his compositions through his use of extended techniques. The Sleeper (1984), one of his few songs for voice and piano, typifies Crumb’s compositional style, with the virtuosic vocal line containing extremes of range, and unusual piano techniques such as pizzicato, glissandi and muted tones. The result is that Edgar Allan Poe’s haunting text is vividly brought to life. Black Angels (1970), for electric string quartet also playing various percussion instruments and bowing small goblets, is one of his most successful pieces. Though thoroughly avant-garde, Crumb’s music is often lyrical and never detached or esoteric. Click here to see the amazing graphic score of Crumb's The Magic Circle of Infinity.

Morton Feldman (1926-1987) was born in Queens, New York City, to Russian Jewish parents. His composition teachers included Wallingford Riegger and Stefan Wolpe. Feldman met composer John Cage in 1949 and, through him, Earle Brown, Christian Wolff and David Tudor. Cage became an unofficial teacher of sorts to the younger composers, and encouraged Feldman to break further away from compositional traditions and forge a new path. Feldman was especially influenced by Cage’s ideas on chance and silence in art. Through Cage he also met artists and writers such as Philip Guston and Frank O’Hara, who became good friends of the composer. Feldman was heavily influenced by visual art, especially the works of Guston, Robert Rauschenberg, Jackson Pollock and Jasper Johns. He admired Ives and Varèse for their apparent lack of methodology. Like Charles Ives Feldman was a businessman, working for the family textile business until 1973, when he was appointed Professor at the University of Buffalo. From the late 1970s the scale of his music enlarged dramatically: his Second String Quartet is 5 hours in length. Feldman married the Canadian composer Barbara Monk shortly before his death of pancreatic cancer in 1987.

Click here to listen to Juliet Fraser sing Three Voices.

Listen to Feldman's only opera Neither, to Rothko Chapel and to Only.

Click here to listen to Juliet Fraser sing Three Voices.

Listen to Feldman's only opera Neither, to Rothko Chapel and to Only.

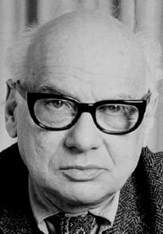

Milton Babbitt (1916-2011) was known for his serial compositions and later for his electronic music. He received one of Princeton's first Master of Fine Arts degrees in 1942. He inherited his father’s mathematical ability, and was a member of the mathematics faculty at Princeton from 1943-45. In 1948, Babbitt returned to Princeton music faculty. In 1973 Babbitt became a member of the faculty at the Juilliard School in New York. He gained somewhat unsought-after notoriety for his essay ‘Who Cares If You Listen?’ which was published in High Fidelity magazine in 1958. The essay has been read as epitomizing the distance between avant-garde composers and their audiences.

Click here to listen to Juliet Fraser sing extracts from Philomel.

Click here to listen to Juliet Fraser sing extracts from Philomel.

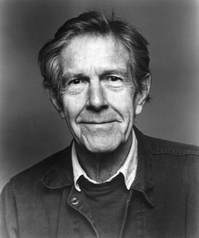

John Cage (1912-1992) grew up in Los Angeles. He studied at Pomona College and then in Europe, where he started to compose and studied with Lazare Lévy. He returned to the US in 1931 and studied with Henry Cowell and Adolph Weiss, a former pupil of Arnold Schoenberg. The Three Early Songs, settings of texts by Gertrude Stein (a writer whose vision was as pioneering as his own), date from this time. In 1933 Cage began to study with Schoenberg in California, at the University of Southern California, and subsequently at the University of California Los Angeles. He then took up a teaching position in Seattle. It was while in Seattle (1938–40) that Cage first gained recognition for his compositions, by putting on concerts of his music for percussion ensemble. He also experimented with works for dance, and his subsequent collaborations with the choreographer and dancer Merce Cunningham sparked a long creative and romantic partnership. Whilst working in Seattle he began to experiment with increasingly unorthodox instruments such as the prepared piano (a piano which has had its sound altered by objects such as nails/coins placed on, beneath or between the strings). He also experimented with using tape recorders, record players, and radios as unconventional musical instruments. E.g. Imaginary Landscape no.4 (1951) for 12 randomly tuned radios. In 1949 Cage met Morton Feldman and the two became great friends. Later Cage, Feldman, Earle Brown, David Tudor and Christian Wolff came to be referred to as "the New York school." Almost all of Cage's music from 1951 onwards was composed using aleatoric procedures, most commonly using the classic Chinese text, the I Ching. In 1952, Cage composed his most famous piece: 4′33″ in which the performer refrains from playing for the duration of the piece and the ambient noises create the piece’s content. In 1962 Cage began to write pieces comprising written instructions without a fully notated score. E.g. The score of 0′00″ (1962), which simply reads: "In a situation provided with maximum amplification, perform a disciplined action." He was also famous for his beautiful graphic scores (abstract images for musical interpretation rather than conventional notes). In the late 1960s Cage began to apply chance procedures to pre-existing music by other composers. E.g Cheap Imitation, written in 1969 and based on the music of Erik Satie. In these works, Cage used the rhythmic structure of the originals and filled it with pitches determined through chance procedures. Cheap Imitation marks return to writing fully-notated works for traditional instruments. Another series of works, the Number Pieces, written in the final five years of his life, make use of time brackets: the score consists of short fragments of music/single notes with indications of when to start and to end them.

Click to listen to Nowth Upon Nacht, A Flower and The Wonderful Widow of Eighteen Springs

Click to listen to Nowth Upon Nacht, A Flower and The Wonderful Widow of Eighteen Springs

Ruth Crawford Seeger (1901-1953) grew up in Jacksonville, Florida. She studied in Chicago where her piano teacher, Djane Lavoie Herz, introduced her to the music of Alexander Scriabin and to composers Henry Cowell and Dane Rudhyar, whose music would exert a strong influence over Crawford’s compositional style. Whilst in Chicago Crawford taught piano to the children of Carl Sandburg, whose poems she set for her Five Songs for Contralto in 1929. 1929 was also the year in which she began studying composition with Charles Seeger, who would later become her husband. In 1930 she became the first ever woman to win the Guggenheim scholarship and went to Paris and Berlin, to study and compose independently (shocking her peers by turning down an opportunity to study with Schoenberg). Crawford’s compositional style can be divided into three phases: the early Chicago years, the New York/Europe years and the Washington years. Her Chicago compositions from the years 1924-1929 are notable for their use of bold dissonances and irregular rhythms, and clearly reflect the influence of Scriabin, Cowell, Rudhyar and Herz. Cowell championed her music, frequently writing about and programming it, and including it his publication New Music Quarterly. The works that Ruth Crawford Seeger wrote in New York and Europe between 1930 and 1933 are perhaps her most famous, and make use of serial techniques and dissonant counterpoint, a system conceived by Charles Seeger that she then developed with him. Her most recognized work is undoubtedly her 1931 String Quartet (listen here). Ruth married Charles in 1932. The couple became increasingly actively politically, and increasingly destitute. They began to fear that avant-garde music had no place in a country ravaged by the Great Depression: "It became almost immoral to closet oneself in one's comfortable room and compose music for her own delight." In 1936 the family was saved from poverty when Charles was appointed to the music department of the Resettlement Administration in Washington DC. Working with Alan and John Lomax at the Archive of American Folk Song at the Library of Congress encouraged Ruth Crawford Seeger’s interest in folk music, and the three became the driving force in the American folk music revival. Over the next two decades Ruth Crawford Seeger abandoned composing in favour of collecting and arranging folk songs. Her arrangements American folk songs are amongst the most widely-adopted in the States and her collection American Folk Songs for Children was became a standard text in primary school music education. She was also the matriarch of a family of celebrated folk musicians: her children Peggy and Mike and her step-son Pete Seeger went on to become well-known folksingers. She returned to her ultramodern roots in 1952 to write her Wind Quintet, a work that combines elements of folk music and modernism. By the time she completed the work she had been diagnosed with intestinal cancer, and died the following year.

Listen to Music for Small Orchestra (1928), Prayers of Steel from RCS's Three Songs to texts by Carl Sandburg (1930-32), and to one of her politically-motivated songs, Chinaman, Laundryman (1932).

Listen to Music for Small Orchestra (1928), Prayers of Steel from RCS's Three Songs to texts by Carl Sandburg (1930-32), and to one of her politically-motivated songs, Chinaman, Laundryman (1932).

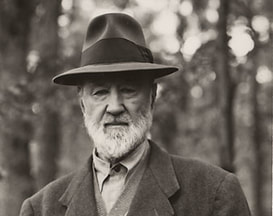

Charles Ives (1874-1954) Drawing on Transcendentalist writings, European poetry and art music, American traditional songs, church music and childhood memories, Ives forged a highly individual style through the most innovative and radical technical means possible. Charles’ father George fostered his son’s interest in techniques such as polytonality and polyrhythms. Indeed, some have suggested that Charles’ experience sitting in the town square in Danbury, listening to his father’s US Army band play at one end of the square while another band was playing elsewhere in the square led to his fascination with polytonality and polyrhythms. Ives became organist at Danbury Baptist Church at the age of 14. In 1894 Ives took up a place at Yale University, studying organ with Dudley Buck and composition with Horatio Parker (Ives quickly tired of the latter’s conformance to convention however). Ives graduated from Yale in 1898 and moved to New York, where he worked as a clerk in an insurance company before forming his own insurance agency with a friend in 1907. He divided his time between business and music, working long hours to the detriment of his health. From 1910 to 1918 Ives was at his most prolific, working on many compositions simultaneously. In 1918 serious heart problems forced him to reduce his workload. He composed little new after 1918, instead revising existing compositions. His vast experimental output eventually brought him recognition as the most influential American composer of his time, and perhaps ever. However, it was not until 1930, when he had all but retired, that his music began to receive the recognition it clearly deserved. Fellow composer Henry Cowell was one of the key figures in giving Ives’ music exposure and recognition, releasing several of his (and Ruth Crawford Seeger’s) works in his publication New Music Quarterly. Further recognition came when Ives was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for his 3rd Symphony, giving his work significant national and international exposure, and leading to his music being championed by prominent conductors such as Leonard Bernstein.

Listen to Ives' Concord Sonata Movement no.3 The Alcotts

Listen to Symphony No. 2, Violin Sonata No. 1, Songs My Mother Taught Me

Listen to Ives' Concord Sonata Movement no.3 The Alcotts

Listen to Symphony No. 2, Violin Sonata No. 1, Songs My Mother Taught Me